Read about the artist behind the short film We Hunt Giants.

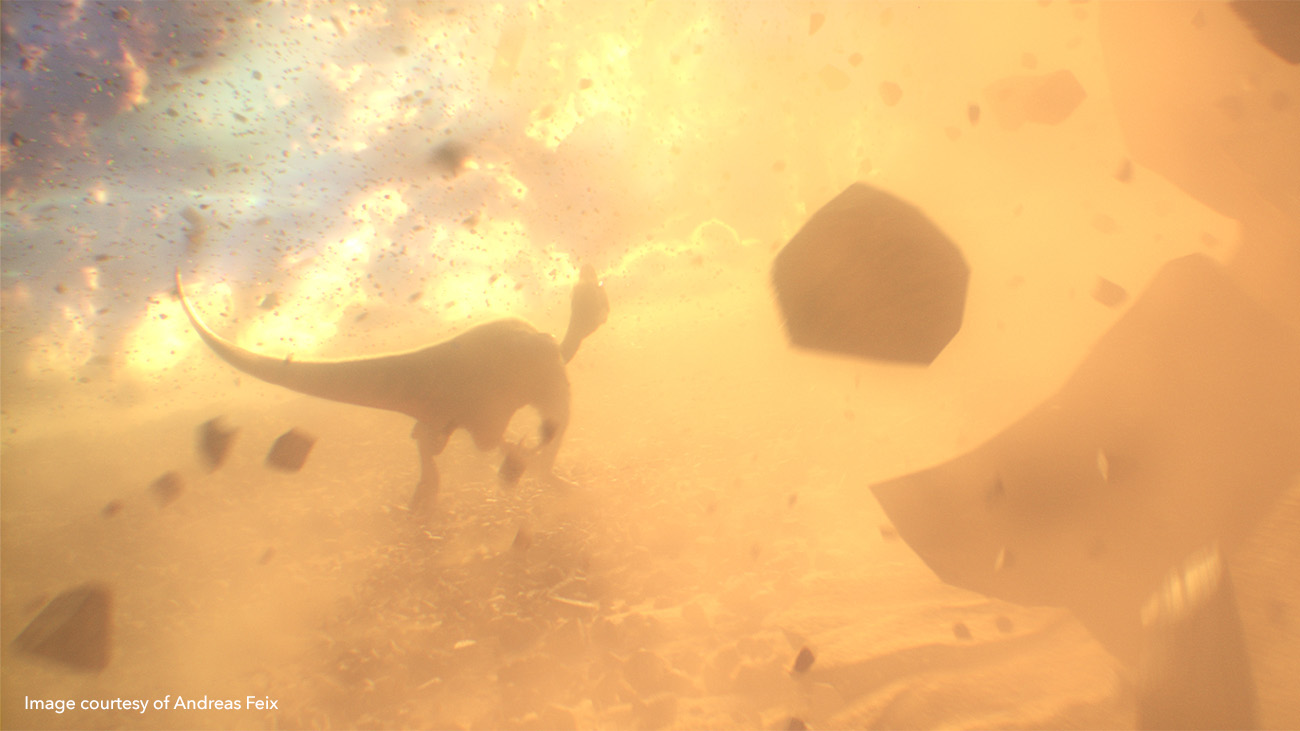

London-based VFX artist Andreas Feix has worked for multiple major studios, and is the visual effects talent behind the independent short film We Hunt Giants, which was featured in our Nuke 16.0 release.

His love for VFX grew from his first viewing of Jurassic Park, leading to a passion for dinosaur design that would eventually see him working on the VFX for the Jurassic World franchise.

For our latest Artist Spotlight, we spoke with Andreas about his career journey, his design inspirations, and how he used Nuke Indie to create the jaw-dropping dinosaur VFX for his short film.

What inspired you to go into VFX?

I watched the original Jurassic Park on a VHS tape when I was six, and my mind was blown. I remember cowering behind a bookshelf by the film’s third act. Although I didn’t understand the process behind it, my interest in filmmaking and VFX grew over time, with the release of the sequels and other big VFX blockbusters and animated films — the ones my parents would allow me to watch. The subsequent release of Walking with Dinosaurs in 1999 fully cemented my interest in VFX and animation, and I started experimenting with short animations at home.

What do you enjoy most about working in VFX?

Creating VFX is a bit like playing the role of a magician. The work we do is either a showpiece to dazzle the audience, or a sleight of hand that keeps the audience guessing how the invisible trickery was done.

It’s continuously inspiring to see the work that other industry peers present. And every new project keeps you on your toes with a fresh set of technical challenges, so there‘s never a dull moment.

Can you tell us about your current role and your path there?

I’m a Senior Compositor at Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), which has been a dream role for me ever since I learned about the studio’s history and impact on the film industry.

I started experimenting with short films at high school, both live-action and stop-motion brickfilms, and later on I landed an internship at Unexpected, a small film and animation studio. This allowed me to study at Filmakademie Baden-Wuerttemberg in South Germany, where I also started using Nuke on various student projects, graduating in 2015.

Over the past 15+ years, I’ve worked for a number of VFX companies in Germany and the UK, including Pixomondo, Mackevision (now Accenture Song), MPC, Framestore, Cinesite, and, ultimately, Industrial Light & Magic (ILM).

What project/s are you most proud of and why?

One of my personal highlights was working on the VFX for Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom. Not just because of the dinosaurs, which is always a personal hook for me, but also my attachment to the original film, which meant that I wanted to push my technical skills and level up the work I’d done. The final film aside, seeing several of my shots featured in the marketing was incredibly rewarding. Another favourite project was Mission Impossible: Dead Reckoning Part One, where I developed several of the iconic mask reveal shots from start to finish.

One project that’s still hard to beat for me is my graduation film Citipati, about a small dinosaur coming to terms with its own death. Taking over two years to complete, this student short was created entirely in CG and finalized in stereo 3D over many sleepless nights. The effort ultimately paid off as Citipati received a ton of accolades over the years. And even a decade later, it’s heartwarming to hear how the film has resonated with people on so many different levels.

How did the We Hunt Giants project begin, and what were your main inspirations?

During the pandemic lockdown, I created a series of clips featuring a small dinosaur in a home video setting, named ‘Tucki’. This caught the attention of indie director Titus Paar, a friend of other filmmakers I had previously collaborated with. He suggested co-creating a short film with dinosaurs, and from the start, I appreciated him giving me an equal say in the development, given the labor-intensive work of the required VFX.

One of our main inspirations for the fantastic setting was the classic Ray Harryhausen movie One Million Years B.C., along with Genndy Tartakovsky’s Primal. We were also influenced by various depictions of ancient tribes and their lack of modern tools and weapons, as the struggle for humans to survive in such a prehistoric world would be much more challenging.

What was your process for developing the dinosaur effects?

It was important to plan everything carefully in advance of the main shoot. Once there was a script, I did a breakdown with some crude storyboards, and later on we created a 3D previz. This meant I had a lot of creative input in designing individual shots, often finding inspiration in my own personal collection of feature films.

Armed with the previz, we had pretty much had every major VFX shot planned and scheduled, as we only had a winter weekend in a Swedish national park for the entire project. Together with the cinematographer, we devised a routine where we would capture additional data for each shot without delaying new setups.

As I’d done a couple of personal dinosaur and creature projects in the past, the goal was to build on previous expertise while also finding ways to elevate the work, such as improving details in the assets and building better simulations.

What kind of references/research did you use for the dinosaurs?

I like to cast a net as far as possible during the research stage. That includes real-world references like drawings and photographs of actual skeletons, various modern creatures for details and behavior, and artistic interpretations such as artworks, models, and previous depictions. Even if certain recreations might not be as accurate nowadays, there’s always some value in them, whether that’s inspiration or further guidance.

When we were initially ‘casting’ the individual creatures, being a dinosaur buff meant that everything was, of course, neatly categorized for each subgroup and species of dinosaur.

Can you tell us about your workflow on this project?

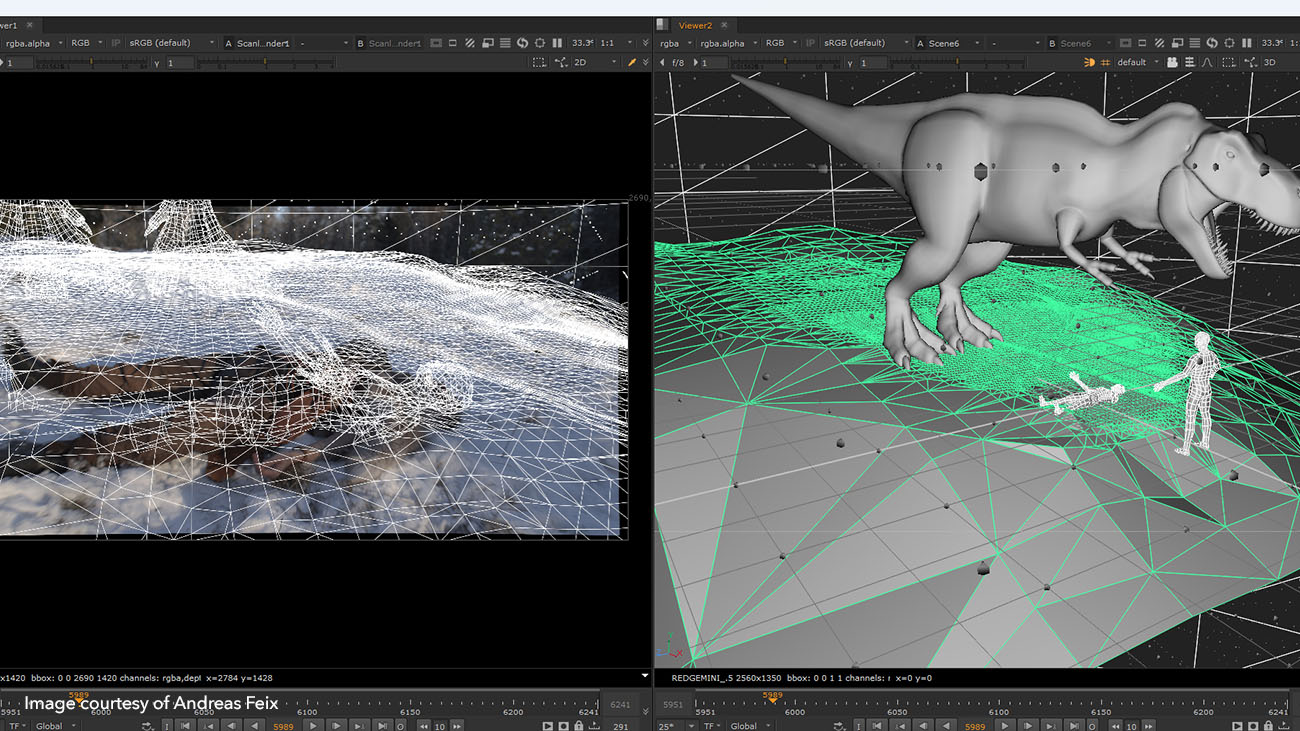

While the plates went into editing, I started building 3D assets for the different dinosaur assets, primarily in 3ds Max and Mudbox, with Houdini for some muscle simulation work, before using Nuke Indie [the Nuke Studio license created specifically for solo artists] to assemble and composite the textures.

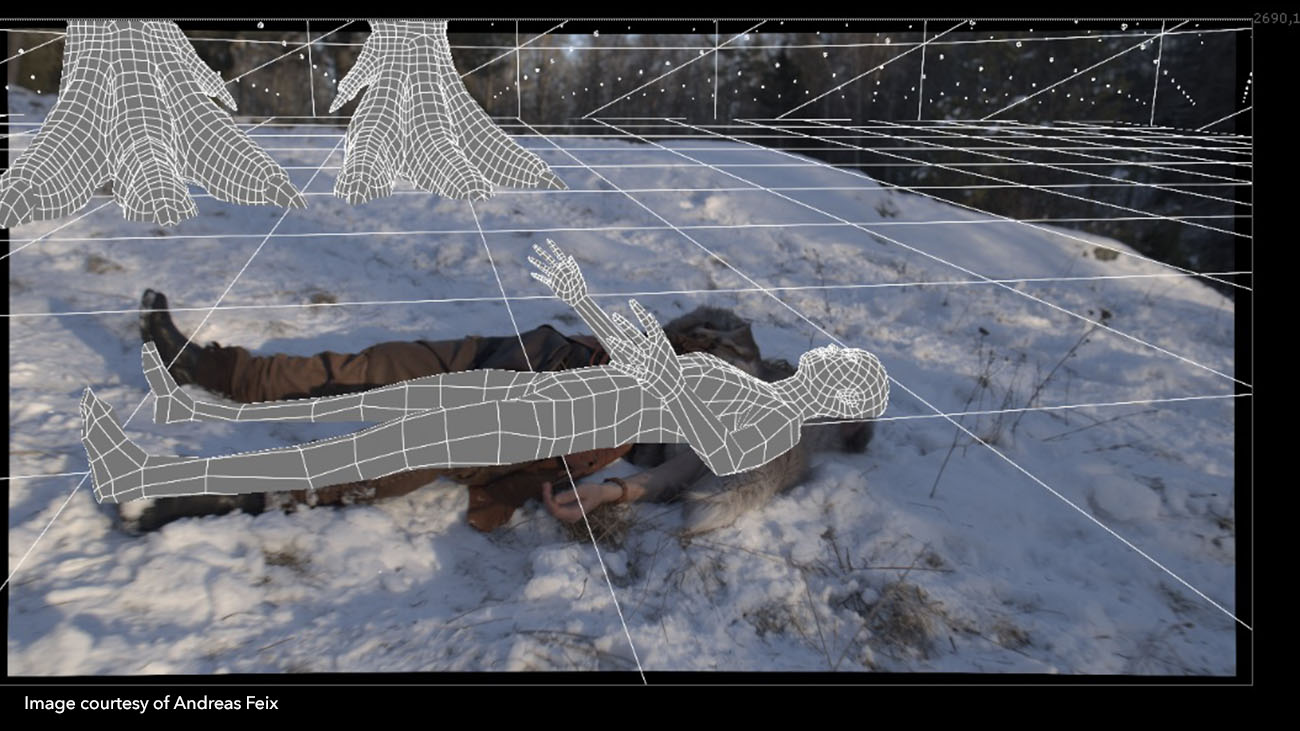

I then imported the edit and raw material into Nuke to write out masters for each individual shot, in the form of EXR sequences. Nuke was also used for all the layout and prep work, matchmoving every shot using the built-in 3D tracking setup, and creating 3D geometry for animation. And of course, Nuke was used for all of the compositing work to finalize the individual shots.

Were there any specific challenges in this project that the software helped you to overcome?

The entire project was a one-man job, VFX-wise, and confined to one personal desktop. Also, time was limited as this was just a side-project to my ongoing work at ILM, so efficiency was very important. 3D renders — done in V-Ray — were effectively restricted to two versions at most, while cutting down on some calculations like motion blur, with the majority of the lighting and shading tweaks done within compositing.

Early on in production, I set up templates so I could rebuild the passes out of V-Ray, with the ability to break each light down to individual shader components. That meant complete control over the look, and the ability to properly re-convert geometry data rendered to directly apply procedural textures, motion blur, depth of field, and filtering with little to no tweaks — streamlining the process and saving a lot on render times.

As with every project, some of the demands change over time from planning to post. In a few graphic shots, we reveal the mangled body of a hunter following a dinosaur attack, even briefly showing part of his face missing. The small amount of SFX makeup only showed a gash on his cheek, so each shot received a digital makeover with a rather tight turnaround. Everything was carried out inside of Nuke — from creating multiple layers of wounds, and shredded cloth and blood patches, to tracking, animating and compositing everything together using a variety of 2D and 3D techniques.

Another case required recreating a shot fully in CG using a digital double, with the environment being built entirely in Nuke using an alternate cleanplate, photogrammetry, and a little bit of machine learning to restore some plate detail. I created the backdrop based on a separate clean plate, and used the DeBlur node to remove some of the motion blur artefacts in the original. That helped create enough detail for a relatively sharp backdrop, which could then receive new, shot-appropriate motion blur on top.

Did you learn anything new while working on this project?

I had to step up and learn about supervising a project from start to finish, as well as building a muscle and tissue system in Houdini for the main dinosaur creature.

Within Nuke itself, I dove more into procedural generation and templates, such as adding texture detail and particles non-destructively with pre-built setups. A good example were smaller touches such as blood and snow coverage on the CG dinosaurs, which were set up as a combination of several noise patterns based on surface data in the 3D renders.

How does it feel to see your own artwork used as part of a Nuke release?

It was a bit of a surprise to see it displayed prominently in the products’ feature showcases across both Nuke and Katana — not just shots but also whole sequences and individual dinosaur assets. It was gratifying as well as humbling, given that you grow attached to any sort of work you produce.

What features or characteristics of Nuke do you particularly value, and why?

I often enjoy treating Nuke like a playground of sorts and I like to tinker with the existing tools, or simple scripting in order to find new creative solutions. For example, tailoring the Views feature — typically in use for stereo workflows — to procedurally composite multiple texture UDIMs of an asset simultaneously, or creating procedural tools based on 3D render data.

Given my background as a generalist, I regularly find myself taking advantage of the various 3D tools such as camera tracking, 3D projections, and particle systems to flesh out my shots or even build them entirely within Nuke, without the need to use another software package.

One of the main advantages is the complexity that Nuke allows when you build your project or script — which is one of the main reasons I started using it — while still being able to handle it flexibly and lay it out visually in the Node Graph.

Nuke also gives you the option to expand on that complexity by other means, like adding sublayers using custom channels, Views, and Multishot setups. You can also tailor your workflow by creating your own custom tools, Gizmos, and templates and share them easily.

What advice would you give to people hoping to break into the VFX industry?

Constantly learn and broaden your horizon, not only to increase your skills but also to expand your perception of the world. Having an interest in film and television is a given, and you should explore them in a variety of forms. Also, keep an eye on how the industry is developing: follow the trends and get inspired by the works of others.

Explore and experiment with the software of your choice and the vast amount of online resources available. But don’t just blindly copy the tutorials: learn the underlying mechanisms instead. This includes stepping outside your comfort zone. Even if you want to specialize in a particular field, gaining experience as a generalist is incredibly helpful as you understand more about the overall pipeline and the role each person is playing.

And don’t forget what level of personal artistry and creativity you can bring to the table. It’s vital to keep that creative spark alive as it’s the greatest motivator for advancing your skills further.

Check out more of Andreas’s work on Eclipse FX.

Explore our library of Foundry Learn tutorials to help you get more out of Nuke. Just starting out? Check out Nuke Non-commercial, which enables you to learn at your own pace, for free. And if you’re a student, head over to our Education page.